Why Tourism is Not a Four-Letter Word

Eric Weiner: On travel snobbery -- and why paying 30 bucks to get pummeled by a guy named Mustafa isn't such a bad thing

03.01.10 | 12:47 PM ET

iStockPhoto

iStockPhotoOn a recent trip to Turkey, two seemingly unrelated experiences got me thinking about a dirty word—tourism—and how terribly under-appreciated it is. Item one: A beefy, mustachioed Turk named Mustafa beats the living daylights out of me and, as I grow ashen and dizzy, douses with me ice water until I perk up, so he can beat me some more. For this, I gladly paid about $30. Mustafa works in a hamam, a Turkish bath.

Item two: About three dozen Turks, dressed in long white tunics, twirl round and round while musicians play a plaintive, haunting melody. It’s a mesmerizing performance that renders the audience silent with awe. The “performers” are sema-zan, whirling dervishes.

What these two events have in common is that they are traditions kept alive (at least in part) with tourist dollars. Three-quarters of my fellow hamam bathers were foreign. I doubt if the business, housed in an elegant 16th-century building, could last a month without us. As for the whirling dervishes, they earn their salary entirely from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Otherwise, their job prospects are grim, whirling not exactly being a growth industry these days.

Tourism gets a bum rap, especially by—let’s face it—travel snobs. You know who I mean. Yes, you who wouldn’t be caught dead at Disney World. Or on a Caribbean cruise. Yes, you with the Moleskine notebook and sourpuss expression. You know who you are.

Travel snobbery is rampant, insidious, and, frankly, annoying. Everyone fancies themselves a traveler, not a tourist. But that’s a lie. The fact is we’re all tourists. Yes, even you, travel snob. Now get over it. It’s not such a bad thing either. We tourists provide jobs and, more than that, keep centuries-old traditions alive. Granted, some of these traditions—the long-necked women of Thailand spring to mind—should probably be allowed to die off, but that is the exception, not the rule.

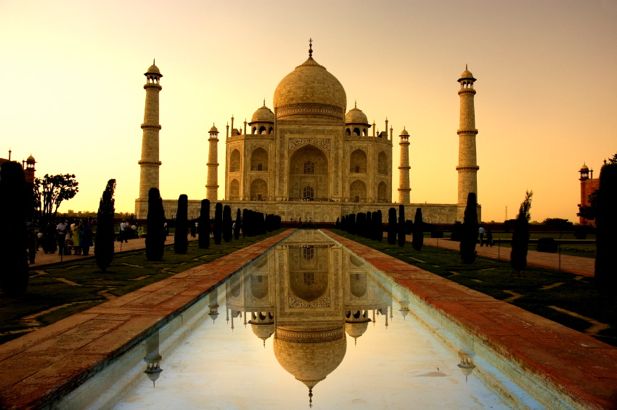

The idea is simple: A culture is worth more alive than dead. The same applies to monuments. In India, foreign tourists pay much more than locals to visit the Taj Mahal. India is asking foreign tourists to, in effect, subsidize their heritage. I don’t have a problem with that. I can afford the extra rupees and, besides, it makes me feel good.

A travel snob might look at the hamam I visited in Istanbul or the whirling dervishes I witnessed in Konya, Turkey, and declare them “contaminated’ by tourism. Well, yes, of course they are. The moment we step foot in a foreign land we change it irrevocably. We tread heavily, whether we’re wearing sneakers or Birkenstocks. Why not do some good while we’re treading?

The fact is that young Turks don’t visit the public baths and don’t care much for the whirling dervishes. Foreign tourists do, though, and that’s not such a terrible thing. Better a slightly “inauthentic” cultural experience than none at all. My dollars are keeping the dervishes whirling and the sadistic Mustafa gainfully employed. That is, I think, money well spent.![]()